Now Playing

Release

09/07/2006 (NL)

09/07/2006 (NL)Director

Nathalie Alonso CasaleCast

Edgar FignerTatiana Tkatsch

Angelika Nevolina

Jevgeni Mercuriev

Daria Konstantinova

Alexander Yudin

Sergei Figner

Producer

San Fu MalthaNathalie Alonso Casale

Co-producer

Joel-Ange KiefferCamera

Vladas NaudziusSound

Sergei LitviakovScript

Jose-Luis AlonsoDialogues

Jana TuminaEditor

Irina GorohovskajaDrama

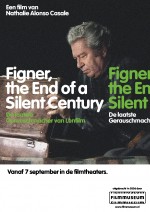

Figner

last survivor of a century of silenceThis is the story of a man saying good-bye to his past. But not just that, since Nathalie Alonso Casale's remarkable film is as much a portrait of Russia during the last, unsettling, century as it is of its cinema as well.

The idealism of the Russian Revolution has dissolved over many years; a time of betrayal yet facing the truth became the lesser evil. People have become lost in the new life they have built. Their lives have proved to be as unhappy as they are dull and escape for many from reality is via the cinema. And, over a period of many years, fictional stories and imaginary celluloid heroes have become so intertwined with the drudgery of daily existence that it isn't always easy to tell one from the other.

The film's central character - Edgar Figner - has worked, with his son, as Russia's principal foley artist in the dream factory of the Lenfilm Studios in St. Petersburg for over thirty years. Thus, he is affected by the daily melange of authentic and illusion becoming even more than anyone else; his world is where fact and fantasy collide.

Figner is nearly seventy years old and at the end of his career: like a master-magician he creates sounds in front of the film screen by performing tricks with ordinary objects. As his nation's leading exponent of this remarkable art-form, Edgar Figner has provided these specialised sound effects for literally hundreds of films.

Day after day, he trudges to the studio carrying his small suitcase that contains the tools of his trade: ordinary every-day objects that enable him to create the sounds required of footsteps in the snow to a door being unlocked; from bird-song to a horseman galloping by in the distance.

Edgar was born in St. Petersburg and has always lived in the same house. Following the October Revolution, his home was turned into a communal flat and had its numerous rooms split up between several families. This communal way of living is a Soviet invention from many years passed, whereby different families lived together; each having their own room but all sharing the kitchen and bathroom facilities.

Edgar kept one room. He married and raised his family in that room, surrounded by paintings and photographs of his ancestors: his Grandfather was a prosperous opera singer while his Great-Aunt was a terrorist who participated in the murder of the Tsar Alexander II. For Edgar, the admirable past of his ancestors is just as important as the present life that has enveloped him.

However, in the Russia of today, the nouveaux riche like to buy up these living quarters for conversion to private use. In exchange, each of the families is provided with a small apartment that creates an illusion of having their own private space. For Edgar, modern life intervenes when his home is bought by one of the new Russian elite, forcing its occupants to move out and threatening to shatter his ties with the past. He doesn't want to leave. In his subconscious, he tries to escape the unbearable reality.

With his suitcase full of his personal belongings he leaves - or dreams he does? - and embarks upon a train journey. Yet, he appears to be on a journey to nowhere and the compartment in which he is travelling curiously resembles the room of a house.

Five passengers share Edgar's compartment. Each becomes a combination of the pictures in his room and from within the films for which he has created foley. It is as if Edgar has brought the dead back to life with each of these characters filling the threatening abyss of his future.

When one of the passengers asks him for an alarm clock, he starts searching in his suitcase. He doesn't find the clock but unearths many other family belongings which lead to stories told by the other passengers. Their tales reflect their own problems and frustrations: the old spinster talks of Isadora Duncan as if the great ballerina was herself; the young widow relates her miserable life as if it was an everlasting love affair while the Second World War veteran recalls the dearest moments of his own failed existence.

These people are the result of a Russia submitted to the yoke of the Soviet regime, carrying its scars inside their souls. And, within Figner: End Of A Silent Century, their stories are illustrated by fragments of classic Russian films that make the interaction visible between cinema and life in the Russia of the twenty-first century.

Jogged by photographs and images, strange events begin to take place. In Edgar's mind, the passengers and their stories become all too real: more than he can cope with. He leaves the train.

Alone with his suitcase and his thoughts, Figner realizes that his soul is no longer a luggage compartment for dead images of other people's past.

Through his job at the studio, reality is further forced upon him. His personal transformation is now hand-in-hand with the drastic changes that have taken place within Russian society itself changes that are also reflected in the films to which he was so connected. Figner finds himself foleying a world that has become as ugly and crude as actuality itself.

He makes one last attempt to get things straight and goes back to his old house. But the corridors that once were overflowing with life have now become empty veins through which flows the distant sound of Figner's own memory.

Entering his room, he discovers that his world has changed once more and that he, himself, has finally become part of it.

Festivals:

International Film festival Rotterdam

http://www.filmfestivalrotterdam.com/

Locarno

http://jahia.pardo.ch/index.jsp

Brisbane

http://www.biff.com.au/

Mill Valley Film Festival

http://www.mvff.com/

Stills